The most wonderful time of the year? Tell that to Wal-Mart.

The world’s largest retailer has long dominated the holiday shopping season, with eye-popping discounts that drew throngs of customers and made life miserable for competitors.

After fresh price cuts this month, few doubted they would own this season, too. But this heartwarming storyline for Wal-Mart has turned into heartburn for the company.

Today, the retailer is expected to announce, based on its own estimates, that sales for November fell for the first time in a decade.

“In a season of what has been pretty healthy numbers from retailers, Wal-Mart has been lackluster, to say the least,” said Adrianne Shapira, an analyst at Goldman Sachs. “Houston, there is a problem.”

But what exactly is the problem?

At first glance, the stumbles seem to resurrect the perennial question: is Wal-Mart too big for its own good, making it impossible to achieve the gravity-defying growth that Wall Street has counted on for four decades.

Yet, what is happening now appears to be more complicated than Wal-Mart hitting a wall. It may simply be changing too fast, acting more like a start-up than a company with 6,000 stores, 1.3 million employees and sales of $312 billion. And that may not be such a bad thing in the long run.

In the last year, Wal-Mart has introduced a dizzying number of new strategies: it started a line of urban fashion, began renovating 1,800 stores, overhauled its advertising to focus less on price and more on style, rolled out $4 generic drugs, ended its layaway program and imposed wage caps on its workers, to name just a few.

Given its size, even the slightest misstep is magnified. And this season, Wal-Mart has made several, alienating shoppers with designer-inspired clothing and disruptive store remodeling.

And when these miscues occur at the same time, as they have recently, they spook not just investors in Wal-Mart — its shares are down 5 percent this month — but the broader stock market as well.

Wal-Mart has little choice but to change, analysts said. The company’s formula since 1962 — pile cheap merchandise high and watch it fly — is no longer enough. Competitors like Target and Best Buy have stolen shoppers with smarter fashions and sleeker electronics, leaving Wal-Mart to sell Americans mostly everyday products like laundry detergent and socks.

And the company’s strategy of growing through relentless store openings — about 300 a year for the last decade — has begun to hurt the retailer as much as help it by siphoning away sales from other Wal-Marts nearby.

The problem shows up in a crucial yardstick of its performance: sales at stores open at least a year, like the November figure that rattled investors.

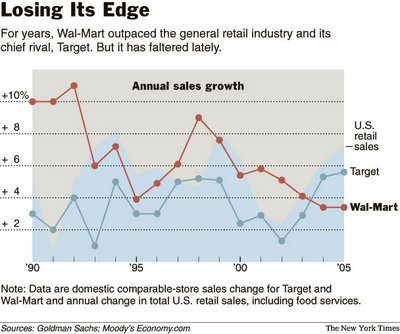

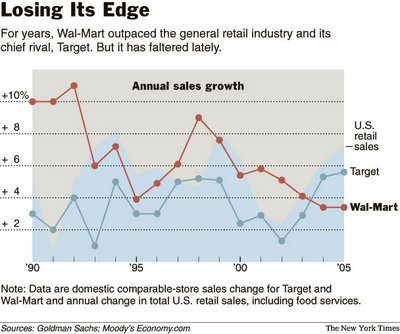

Since the beginning of 2006, Wal-Mart’s monthly sales have risen 2.4 percent, half as fast as Target, which posted a 4.8 increase.

Wall Street has been urging the company to find a solution to the slide.

“They need to take some risks,” said Christine K. Augustine, an analyst at Bear Stearns, who expressed alarm at the company’s November performance. “I do not fault them for trying new things.”

But the turnaround effort — which the company has dubbed “Wal-Mart Out In Front” — is taking longer than investors had hoped. And there is a growing consensus that the rapid pace of change may be one reason why.

Individually, the strategies can be viewed as healthy fixes to longstanding problems at Wal-Mart. Trendier (and pricier) clothing, for example, will theoretically persuade consumers to spend more at Wal-Mart, rather than, say, Kohl’s. Ending layaway plans and capping wages will save the company money.

Collectively, however, these measures have created the retail equivalent of cacophony in the stores, temporarily disorienting consumers and employees at a crucial time of year.

For example, at the same time that Wal-Mart introduced fur-trimmed jeans in the clothing department and 42-inch flat-screen televisions in the electronics section this year, it also began renovating hundreds of stores, “making it difficult to find all that enticing new stuff,” Ms. Augustine said.

“They are working at cross purposes over a short period,” she said.

Wal-Mart executives have conceded that the company’s efforts to reinvent itself have hit a few snags.

Several weeks ago, H. Lee Scott Jr., the chief executive of Wal-Mart, told analysts that he was “surprised that the disruption that occurred during the remodels was as extensive as it has been.”

The new clothing at Wal-Mart created problems, too. After early success with a designer women’s clothing line called Metro7 in 600 mostly urban area stores, the company rolled out the fashions across the chain.

It did not work. The average Wal-Mart shopper lives in the suburbs, is roughly 5-foot-2 and wears a size 14 — making them poor candidates for the skinny jeans that were a popular, tight-fitting fashion in urban markets.

Consumers like Shirley Shepherd, who lives outside Salt Lake City, Utah, balked at the unfamiliar clothes.

“I would never buy dress clothes here,” said Ms. Shepherd, who shops at the Wal-Mart in Midvale, Utah, twice a week for staples like toothpaste, batteries, underwear and socks.

It’s not just a simple matter of new fashions not selling well. The new clothes took up space where Wal-Mart stocked reliable sellers like basic blouses and sensible skirts. So the entire apparel department suffered, contributing to the November sales drop.

Mr. Scott said the company moved “too far, too fast” with the Metro7 clothing line and will now sell it only in its urban stores.

By ending layaway plans, which allowed low-income shoppers to make purchases in installments, the chain freed up the store space and employees.

But it also upset shoppers like Michele Kahindi, a 30-year-old mother of three who lives in Portland, Ore.

Eliminating the program “hinders a mom’s ability to hide stuff from the kids,” she said. “I don’t get it. Now Kmart is going to get my layaway business.”

Some of the changes at Wal-Mart have worked.

Higher-priced electronics have been a hit. By offering products like flat-panel televisions, cellphones and MP3 players at several prices — including a $3,000 plasma-screen TV — Wal-Mart has tripled sales in some stores, proving that consumers will buy upscale products at the chain.

The way the company manages its work force has also helped its bottom line. For example, it is relying on more part-time workers and asking them to be available at night and on weekends when checkout lines are longest.

Sprucing up stores, while temporarily frustrating to shoppers, has improved sales, the company said.

But the company’s hope for a turnaround in store sales could take at least a year, if not longer, for several reasons.

It is too late to cancel the latest orders for Metro7, meaning hundreds of stores will be saddled with the slow-selling fashions for months. Renovations, on hold for the rest of the holiday season to make shopping easier, will start up again in January.

And Wal-Mart said it is still grappling with the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, which the company has said is skewing its sales figures.

Bigger spending by victims of the storm, who received federal funding to rebuild, increased sales at the chain last year, making it harder for the company to improve on last year’s performance. (In November 2005, for example, Wal-Mart’s monthly sales rose 4.3 percent.)

Analysts also noted that a separate Wal-Mart strategy should improve the company’s fortunes. In October, it said it would begin to apply the brakes on new store growth in part to focus more on improving the performance of its existing outlets.

In a small but symbolically important adjustment that will result in enormous cost savings, the company will expand its square footage at a rate of 7.5 percent in 2007, down from 8 percent in the last several years,

For now, Wal-Mart’s message to investors and customers appears to be the same as the one on the signs in its renovated stores: please excuse our appearance — and performance — while we are under construction.

“The size of the undertaking,” said Ms. Shapira of Goldman Sachs, “should not be overlooked.”

Brian Libby contributed reporting from Portland, Ore., and Martin Stolz from Midvale, Utah.

Wal-Mart's entry into the Indian market will receive a huge lift with the announcement of a $7 billion investment by Bharti.

Wal-Mart's entry into the Indian market will receive a huge lift with the announcement of a $7 billion investment by Bharti.